Shooting Napoléon

or: How do you end up with a 290-hour film?

September 1923

Gance writes a proposal for a six-film series covering the life of Napoleon Bonaparte. Each episode is to contain 1.700 metres of celluloid – 75 minutes of screen time. Gance wants to take the commercial model of serial distribution and use his films to expand the artistic horizons of cinema. […]

March-July 1924

Gance creates the first of his six projected screenplays. He is permitted to work in Napoleon’s rooms in the palace of Fontainebleau. […]

August-September 1924

Gance is still hunting for a man to play Napoleon. His friend Albert Dieudonné is dieting on green beans to regain the body of a younger man. One evening he arrives in costume at Fontainebleau, where a stunned elderly attendant mistakes him for the Emperor’s ghost. Marching inside, he recites one of Napoleon’s speeches to an equally startled Gance. Dieudonné is given the role. […]

January 1925

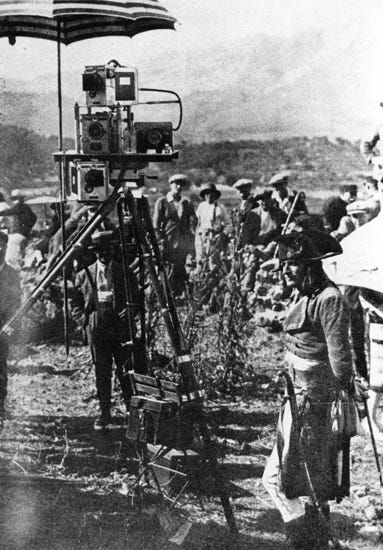

A month after the contracted completion deadline, the first scenes are filmed at Billancourt Studios in Paris. Cameras are attached to the chest of operators so they can walk; wheeled on tricycles so they can track, or on rails so they can slide down stairs; made to capture multiple scenes on the same strip of celluloid so that they seem to possess polyphonic vision. More cameras record the filming process. Gance encourages his actors with every means necessary: whispered instructions, mimed gestures, smiles, pistol shots.

February 1925

Gance receives a telegram: SNOW HAS FALLEN. The production heads to Briançon to film Napoleon’s school snow-fight. Cameras are hurled into action: attached to guillotines mounted on sleds so they can swoop; stuck on rotating tripods so they can turn 360 degrees.

April 1925

The production arrives in Corsica. A mayoral election is imminent in Ajaccio, where the past seems uncannily close to the present. One of Gance’s extras turns out to be the grandson of a man who helped Napoleon evade arrest on Corsica in 1792. Many locals are acting as if Dieudonné is Napoleon. Officials in Ajaccio beg the actor not to wear his hat in public, lest he excites too many tempers. During filming, crowds still loyal to Corsica’s most famous son refuse to shout «Death to Napoleon Bonaparte!» At the end of location shooting, the Bonapartist candidate is elected mayor of Ajaccio. Dieudonné is made an honorary citizen. [… ]

February-March 1926

At Billancourt, Gance is re-enacting the night-time climax of the Siege of Toulon in 1793. Many extras are from the nearby Renault factory, which is on strike. Conditions are realistically grim, but Gance inspires the cast. Rain is provided by the fire brigade, wind by aircraft propellers, gunfire by packs of magnesium. A box of ammunition catches light, triggering a huge explosion. Gance and eight others are engulfed by flames. The victims are rushed to hospital with severe burns. A week later – covered in bandages – the director resumes work.

March 1926

Gance is directing a scene in which a crowd is taught La Marseillaise. He is observed exciting his extras into a state of frenzy by making them sing the national anthem 12 times «in crescendo». The critic Emile Vuillermoz thinks they are «possessed» and frets that Gance might use this wild mob to storm parliament and proclaim himself dictator. Another journalist calls the director a god-like magician presiding «over this birth of Christ». In live exhibition, a singer will synchronise his voice with that of Rouget de Lisle on screen – and Gance encourages theatres to distribute printed copies of La Marseillaise so that the audience can join in.

April-May 1926

For the riot in the National Convention, Gance tells a reporter that he is going «to bring the Mediterranean into the studio». This scene is to be intercut with Napoleon at sea, forming a «Double Tempest». Cameras are mounted on huge pendulums to swoop over the heads of extras; Gance wants spectators to become «a wave in the ocean». Below, cameramen are stumbling in the seething crowd and dodging punches. Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer is on set, watching with alarm as the two parties of extras inflict blows that are more than just historically accurate. Several people are taken away on stretchers.

Gance seems delighted.

July 1926

The population of La Garde in south-east France watches a column of troops march into town. One local presumes they have arrived to invade Italy and fight Mussolini. When informed the man in charge is not Marshal Foch but General Bonaparte, the man shrugs and mutters, «Bah, Parisians…» as he retires indoors.

August 1926

Gance is filming the last scenes of Napoleon in colour and in 3D, but he is more excited by an invention of his own design. Three cameras are mounted on top of one another – each covering one third of a massive panorama: a revolutionary concept that will require cinemas to install a screen three times the normal width together with three synchronised projectors.

September 1926

The production is over. Gance’s assistant Jean Arroy is forced to face reality. He feels as though he has been «jettisoned in an alien century»: modern Paris seems «dull» and «lugubrious» compared to the 1790s.

October 1926

[Gance] and his chief editor Marguerite Beaugé are in a studio overflowing with celluloid. Napoleon has consumed 400.000m of film stock, providing 290 hours of raw material. Their Herculean labour lasts day and night, week after week, month after month. Gance’s retina is impaired for life. Beaugé has a nervous breakdown.

From: Paul Cuff, «The Man of Destiny», in Sight and Sound, December 2016.